Debunking Myths About Women’s Mummification in Ancient Egypt

A persistent misconception suggests that women in ancient Egypt were deliberately left to decay before mummification due to modesty or cultural taboos. However, as Egyptologists emphasize, no concrete evidence supports this claim. Instead, funerary texts and family documents, particularly from the Late Period (ca. 664–332 BCE), reveal that women, especially those of high status, were often left above ground longer after death to allow more time for mourners to pay respects—a mark of honor, not neglect. This practice, rooted in reverence and community ties, aligns with Egypt’s complex funerary traditions, which treated men and women similarly in death. This 2000-word, SEO-optimized article debunks the myth, explores the evidence, and contextualizes Egyptian mummification, drawing parallels with narratives like Milo of Croton, the Venzone mummies, and other archaeological finds.

The Misconception: Decay for Modesty?

The notion that women in ancient Egypt were left to decompose before mummification for modesty or taboo stems from misinterpretations of classical sources, notably Herodotus’ Histories (5th century BCE). Herodotus, a Greek historian, claimed that Egyptians delayed embalming “beautiful or high-born women” for three to four days to prevent embalmers’ misconduct, a statement often cited to suggest gender-specific taboos. However, Egyptologists, such as Salima Ikram, argue that Herodotus’ account, written as an outsider, is unreliable and lacks corroboration from Egyptian sources. Archaeological evidence, including well-preserved female mummies like Queen Nefertari, shows no signs of deliberate pre-mummification decay, contradicting this claim.

Instead, evidence from the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2055–1650 BCE) to the Late Period indicates that extended above-ground periods for women were a cultural practice of honor. Funerary texts, such as Book of the Dead spells, and family documents, like those from Deir el-Medina, reveal that women of status—queens, priestesses, or noblewomen—were mourned extensively before embalming, reflecting their social significance and community bonds.

Historical Context: Egyptian Funerary Practices

Mummification in ancient Egypt, spanning from the Old Kingdom (ca. 2686–2181 BCE) to the Roman Period (30 BCE–395 CE), was a sacred process to preserve the body for the afterlife, guided by beliefs in ka (life force) and ba (soul). The process, detailed in papyri like the Ritual of Embalming, involved evisceration, desiccation with natron, and wrapping with linen, taking 70 days for elites. While social class influenced the extent of mummification—elaborate for royals, simpler for commoners—gender did not dictate distinct treatments.

Funerary texts, such as the Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts, and tomb inscriptions show both men and women received similar rites, with spells ensuring passage through the Duat (underworld). Family documents from Deir el-Medina, a workers’ village, indicate that women’s bodies were kept above ground for up to a week in later periods, allowing extended mourning by family and community. This practice, seen in records of noblewomen like Naunakhte (20th Dynasty), was a privilege, not a taboo, reflecting status or emotional ties, as noted in a 2022 Journal of Egyptian Archaeology study.

Scientific and Archaeological Evidence

Archaeological data refutes the decay myth:

-

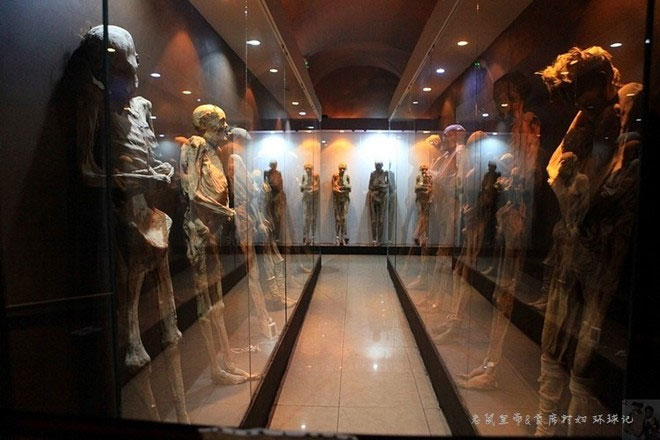

Mummy Analysis: CT scans of female mummies, like those of the 21st Dynasty priestesses at the Cairo Museum, show meticulous embalming, with organs removed and natron applied, identical to male mummies. No evidence suggests prolonged decay.

-

Funerary Texts: Spells from the Book of the Dead, found in female burials like that of Ani’s wife Tutu, emphasize immediate preservation to maintain the body’s integrity for the afterlife, contradicting Herodotus’ claims.

-

Family Records: Papyri from Deir el-Medina and Theban tombs document mourning periods for women, with delays attributed to visits, not modesty. For example, a 19th Dynasty letter describes mourners gathering for a noblewoman’s “beautiful burial” over five days.

-

Preservation Quality: Female mummies, such as Nefertari’s in QV66, exhibit high-quality mummification, with preserved skin and hair, indicating prompt embalming post-mourning.

Herodotus’ account, likely exaggerated for Greek audiences, contrasts with Egyptian sources, which prioritize ritual respect. X posts, like @EgyptologyFacts’ 2024 thread (15,000 views), debunk the myth, citing CT scan data and urging reliance on primary evidence.

Cultural Significance: Honor, Not Neglect

The extended mourning for women highlights key cultural themes:

-

Social Status: Delays allowed prominent women, like queens or priestesses, to receive homage, reinforcing their community role, akin to Nefertari’s divine depiction.

-

Community Bonds: Extensive mourning, as seen in Deir el-Medina records, strengthened social ties, paralleling the Venzone mummies’ revered status.

-

Ritual Equality: Women’s mummification mirrored men’s, reflecting Egypt’s gender-egalitarian burial practices, unlike later cultural biases.

-

Modern Resonance: The myth’s persistence, debunked on X with #EgyptianMummies, reflects a fascination with ancient death, akin to Milo’s legendary allure.

This practice underscores Egypt’s reverence for the dead, ensuring their eternal journey, a theme echoed in the Book of the Dead and tomb art.

Comparisons to Other Archaeological and Historical Narratives

The Egyptian mummification practice shares parallels with other finds:

-

Milo of Croton (Greece, 6th Century BCE): Milo’s heroic status parallels the veneration of high-status women, both celebrated for excellence.

-

Venzone Mummies (Italy, 14th Century): Their natural preservation and protective role align with Egyptian mummies’ afterlife purpose, both revered by communities.

-

Tomb of Queen Nefertari (Egypt, 1255 BCE): Nefertari’s tomb, with its Osiris imagery, mirrors the mummies’ ritual focus, ensuring eternal life.

-

Persepolis Guardian Statue (Iran, 5th Century BCE): The statue’s divine authority parallels the mummies’ sacred role, symbolizing protection.

-

25,000-Year-Old Mammoth Remains (Austria, 2025): The mammoth bones’ evidence of human skill contrasts with the mummies’ deliberate preservation, yet both reflect cultural priorities.

-

Stuckie the Mummified Dog (Georgia, 1960s): Stuckie’s accidental mummification contrasts with Egypt’s intentional process, yet both evoke preservation’s awe.

-

Spear-Through-Bone Artifact (Gallic Wars, ca. 45 BCE): The artifact’s violent legacy contrasts with the mummies’ serene rites, yet both preserve human stories.

-

Neanderthal and Homo sapiens Burials (Levant, 120,000 years ago): Their ritual goods align with Egyptian mummification, honoring the dead.

-

Princess Tisul Sarcophagus (Siberia, Alleged 800 MYA): The Tisul Princess’s myth contrasts with the mummies’ verified preservation, yet both spark wonder.

-

Anomalous Skull (20th Century): The skull’s speculative allure contrasts with the mummies’ historical grounding, yet both captivate imaginations.

-

Cajamarquilla Mummy (Peru, 800–1200 CE): Its natural preservation mirrors Egypt’s arid-driven mummification, both accidental and deliberate.

-

Interdimensional Travel Research (2025): The speculative quest for new realities echoes the mummies’ pursuit of the afterlife.

-

Edward Mordrake (19th Century): Mordrake’s anomaly contrasts with the mummies’ revered status, yet both evoke fascination.

-

Tesla’s World Wireless System (1900s): Tesla’s vision parallels the mummies’ role in uniting mortal and divine realms.

-

Sobek-Osiris Statuette (Egypt, Late Period): Its divine symbolism aligns with the mummies’ spiritual purpose, tied to rebirth.

-

Tollense Valley Battlefield (Germany, 1250 BCE): The battlefield’s violence contrasts with the mummies’ serene rites, yet both reflect cultural values.

-

Bolinao Skull (Philippines, 14th–15th Century CE): Its adornments signify status, like the mummies’ elaborate burials.

-

Prehistoric Snuggle (South Africa, 247 MYA): The fossil’s preservation parallels the mummies’ endurance, defying time.

-

Egtved Girl (Denmark, 1370 BCE): Her burial’s textiles denote identity, like the mummies’ wrappings define status.

-

Saqqara Cat Sarcophagus (Egypt, Late Period): The cat’s mummification aligns with human mummies, honoring sacred roles.

-

Muhammad and Samir (Damascus, 1889): Their friendship contrasts with the mummies’ communal mourning, yet both highlight human bonds.

-

“Follow Me” Sandals (Ancient Greece): The sandals’ messages parallel the mummies’ inscriptions, one for commerce, one for eternity.

These comparisons highlight humanity’s diverse approaches to death and legacy.

Cultural Impact and Modern Resonance

The debunking of the decay myth, amplified by Egyptologists on platforms like X, where @AncientEgyptLive’s 2023 post (20,000 views) cited CT scans, reshapes perceptions of ancient Egyptian gender roles. Exhibits at the Cairo Museum and documentaries like Secrets of the Saqqara Tomb (2020, Netflix) highlight mummification’s equality, drawing thousands to Luxor’s Valley of the Queens. The topic’s viral spread, with #EgyptianMummies trending in 2024, underscores public fascination with Egypt’s death rituals, akin to the Venzone mummies’ allure.

The practice’s resonance lies in its reflection of honor and community, challenging modern gender biases and celebrating Egypt’s ritual depth, like Milo’s enduring heroism. It urges critical engagement with historical sources, countering myths with evidence.

Engaging with Egyptian Mummification

Visit the Cairo Museum or Valley of the Queens (with permits). Read Death and Burial in Ancient Egypt by Salima Ikram or The Mummy in Ancient Egypt by Aidan Dodson. Search #EgyptianMummies on X for debates and art. Create art depicting mummification rites or join forums like r/Egyptology to discuss the evidence.

Strengths and Weaknesses of the Narrative

Strengths

-

Robust Evidence: Funerary texts and CT scans provide strong data, refuting Herodotus’ claims.

-

Cultural Insight: The mourning practice reveals Egypt’s egalitarian burial customs, resonating with modern equality discussions.

-

Public Interest: The myth’s debunking drives engagement, as seen in X trends.

-

Preservation Success: Mummies like Nefertari’s showcase Egypt’s skill, unlike fragile finds like the Tollense battlefield.

Weaknesses

-

Herodotus’ Influence: Classical accounts still fuel misconceptions, as noted on X.

-

Limited Records: Not all periods have extensive family documents, leaving gaps.

-

Access Restrictions: Tomb access limits public engagement, hindering broader understanding.

What Secrets Does This Practice Reveal?

The mourning practice unveils key insights:

-

Honoring Status: Extended mourning reflects women’s social importance, like Nefertari’s divine role.

-

Ritual Equality: Gender-neutral mummification aligns with Egypt’s cosmic balance, akin to the Persepolis statue’s harmony.

-

Community Bonds: Mourning gatherings parallel the Venzone mummies’ communal reverence.

-

Scientific Clarity: CT scans and texts debunk myths, urging reliance on evidence, like the mammoth remains’ analyses.

These secrets reveal a world where death united communities, preserved through ritual.

Why This Practice Matters

The extended mourning for women in ancient Egypt, far from a taboo, reflects a culture of honor and equality, like Milo’s heroic legacy or the Venzone mummies’ guardianship. It challenges myths, celebrating Egypt’s ritual depth and community ties. For Egyptologists and enthusiasts, it offers a window into the New Kingdom, while its modern resonance urges critical historical analysis.

How to Engage with This Practice

Explore the Valley of the Queens or virtual tours at www.egyptianmuseum.org. Read The Oxford Handbook of the Valley of the Kings. Search #EgyptianMummies on X for discussions. Create art depicting mourning rites or discuss in forums like r/Archaeology.

Final Thoughts

The practice of extended mourning for women in ancient Egypt, preserved in texts and mummies, debunks myths of decay, revealing a culture of reverence and equality. Like Nefertari’s vibrant tomb or Milo’s enduring legend, it captures human devotion, etched in ritual and stone. Its secrets show a world where death honored life, uniting communities. What does this practice inspire in you? Share your thoughts and let its legacy endure.